The Lockdown Film Festival: A refusenik recommends

Posted in Uncategorized on April 12, 2020 by uncontrollabledancingwater is meaningless without ships (2011)

Posted in Releases on August 23, 2014 by uncontrollabledancing“Water is meaningless without ships and that bespeaks harbours to haven them, and men and cargoes. What I have written does not pretend to poetry. It only says what it seemed could be said. … ” – ‘Wellington Harbour’, Denis Glover

the sound component to this film includes a re-reading of the poem Le Tempestaire, written in 2010 while I was living in Wellington, where I had a habit of walking along the waterfront. The title of the poem references Jean Epstein’s cinema, the title of the film the once-removed echo of that waterfront, which New Zealand writer Denis Glover also looked out onto, from his room in the hillside suburb of Mt. Victoria, while writing the 1974 book of poems, Wellington Harbour.

Le Tempestaire’s formal structure includes snatches of songs in between lines, like a song half-heard while walking past a café, which ghosts through memory but doesn’t stick around long enough to embed itself as a refrain, functioning more like a radio going off-frequency, the poem a porosity of listening-to-language which folds more recognisable texts into its universe.

water is meaningless without ships repeats this process again, with the (de-sequenced) poem itself acting as a ghost of a refrain within the transmitted sound. this sound also plays with the idea of natural sound within the cinematic space, both by literalising a disjuncture found within the radiophonic medium between voice and presence, and also by responding to the visual space’s depiction of a field-trip to Kinglake, originally intended as a foray to gather field-recordings, which became a confrontation with silence upon the realisation that the whole area had been burnt out by bushfires.

– Sally Ann McIntyre, 2014

http://inexcessofthegivenimage.blogspot.co.nz/2010/11/le-tempestaire.html

For me, I was partly conceiving the work as an internal conversation around how cinema both responds to and generates both memory and narrative. Cinema always builds a kind of narrative, no matter whether it’s chosen or avoided as a strategy, and I’ve always been more interested in how cinema’s relationship to the recording apparatus meant films could be divided into two tracks in terms of narrative: The closed and the open, or the single meaning as opposed to the multiple.

The dominant forms are always assidiously concerned with providing only a single possible reading, and become readily obsessive about that precision – for instance in the way that scriptwriting for Hollywood has been captured for a long time by the post Syd Field et al camp that dictates which minute of a film certain structural devices should occur. This is a necrotising process, that kills the expressive possibilities of the form, and replaces it with both a failed attempt at the artificiality of forms that are not specifically linked to the ontologies of the form (literature, theatre), and a commodity that can be more readily exploited and controlled by its funders.

Of course – as Robert Bresson or Jean Eustache will testify in their very different ways – the form is more robust and more complicated than that. Indeed part of the problem with cinema is that even the most cynical operation of the industrialised form cannot completely dampen the extra-narrative qualities of cinema, so even work that does attempt to squash the life from the form will often fail to do so, as long as some recording element remains. (Whether this is something that occurs with purely digitally generated work is still a moot point, for this argument I’m talking about cinema within the context of the cinematic apparatus of camera, sound recording device and editing device).

However the more interesting films and the more interesting process for me has always been in terms of the cinematic open text. Because an audience viewing cinema will always relate to it as a potential narrative, this means there is less need to construct a narrative, unless your approach is to dictate what response you will get. I’ve never wanted to do that, it seems much more interesting to create work to whom every audience member can have a different response than when where you impose their response upon them. (Obviously there’s a politics to this perspective too). So part of the idea is to understand cinema as being a system for building work of essentially infinite potential meaning, because every audience member will have their own response.

So the idea of this kind of work is not to dictate in advance what the meaning is, but to allow the space for the meaning to permeate through the juxtapositions in the work. In this case, my images of travelling to the silence of a dead forest a couple of hours out of Melbourne gently settle into a kind of stability next to Sally’s field recordings and reworkings of poetry through the Radio Cegeste station transmitter.

– Campbell Walker, 2014

Made in Melbourne, June 2011

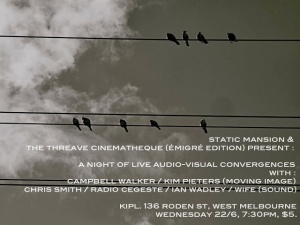

First screened as a live cinema piece at KIPL gallery, West Melbourne, June 22, 2011.

Screenings:

For a few leaves more, The Threave Cinematheque, Dunedin, November 29, 2012.

KIPL: Postmortemism #003, Westspace, Melbourne, February 14, 2013.

Dunedin Film Society, Dunedin, August 28, 2013.

Untitled Dunedin Feature excerpt #2 – “Somewhere really good”

Posted in Uncategorized on February 12, 2012 by uncontrollabledancingThis is the penultimate scene for the film. It’s a long – 50 minutes at the moment – a scene walking through Otago Uni at magic hour. Crazy shooting conditions – wind whistling through the place, totally freewheeling improvised scene, but it turned out wonderfully – one take a few cuts, 93% shooting ratio, one of the best scenes I’ve ever shot I think. Sometimes you get lucky..

Sound recorded – on two zoom H4Ns – by Sally Ann McIntyre. Shot by myself. The actors are Kiti Beech and Jim Currin. This is a nearly 5 minute excerpt. I’m pretty keen on it.

Busy editing now.. It could be a pretty long film… further exceprts will be forthcoming soon.

First footage from new Dunedin based feature…

Posted in Uncategorized on January 15, 2012 by uncontrollabledancingWe haven’t got a title yet, but we’re two thirds of the way through shooting a new drama feature, devised with Jim Currin, and featuring him with Dell McLeod, Maya Turei and others. Shooting more this week… Here’s a small sample scene, featuring Jim and Maya

More to come soon…

Getting Rid of the Albatross / Watching Love Dry: Collected / selected filmworks directed by Campbell Walker

Posted in Uncategorized on September 9, 2011 by uncontrollabledancingA small but intense retrospective -a burst of 4 features in 2 days (and a few shorts) directed by recent Dunedin immigrant Campbell Walker between 1997 and 2011…

Wednesday 14th September 2011

Uncomfortable Comfortable (1999) 6 30 plus Three Nights(1997)

Why Can’t I Stop This Uncontrollable Dancing (2003) 9.00

Thursday 15th September 2011

Little Bits of Light (2005) 6.30

Broken Black Lines (2009) 9.00 plus W Lead (2010) and Town of Damnation (2010)

Campbell Walker: a bio

“A unique New Zealand cinematic voice – Achieves a kind of integrity and truth really seen on screens, uncluttered by any sense of artificiality” – Lumiere Reader, 2005

“An uncompromising role model for a new generation of young New Zealand digital film-makers” -NZ Listener, 2003

“Kind of a prickly, enfant terrible of New Zealand cinema” – NZ Herald, 2005

[choose any three statements]

Campbell Walker is a filmmaker

Campbell Walker makes digital features

Campbell Walker makes relationship films

Campbell Walker makes long slow tortuous films about intimate human interactions

Campbell Walker makes tersely languorous films about the way we interact as New Zealanders from well outside the power structures of film making in New Zealand

Campbell Walker is interested primarily in the possibilities of using cinematic time and space, sound and image, to reflect upon the complexities of culture and human interaction along an axis of realism

Campbell Walker is only interested in acting and has no interest in the camera

Campbell Walker makes ugly cheap films that grind the viewer’s face in the unentertaining minutiae of everyday life

Campbell Walker worked in a video shop in Wellington for ten years

Campbell Walker is an Aro Valley filmmaker

Campbell Walker lives in Dunedin

Campbell Walker is not a normal New Zealand filmmaker

Campbell Walker makes films about being a New Zealander

Campbell Walker will tell you too much about his intimate life

Campbell Walker plunders and loots his own life for material to make films from

Campbell Walker makes personal but fictional films

Campbell Walker just makes it up as he goes along

Campbell Walker is struggling to write a succinct yet definitive version of himself.

“in their utterly different ways, Peter Jackson and Campbell Walker represented the changes in New Zealand cinema and the threats to the viability of moderately budgeted, conventionally shot feature films” Frank Stark in New Zealand Film: An Illustrated History, 2011

“LittleBits of Light at the Paramount. Tortuous. I can’t think of another way to describe this latest effort from Campbell Walker. The Film Commission finally gave him some money to make a film and he makes one of the most depressing and humourless films ever created. “ – Hakopa.com, 2005

“First, you get mellow, as Woody Allen once said, then you get ripe, then you fall off the tree. It is not a process likely to happen any time soon to Wellington film-maker Campbell Walker, who does a good line in prickly intensity. “Most people,” he says, “make movies about the kind of events that change people’s lives. My films are about events that can spoil your week.” Meaning, there are no fireballs or car chases in his movies. Nor do the likes of Meg Ryan and her adorable puppy meet the likes of Tom Hanks in his adorable sweater. Life, and good movies, are not like that.

What Walker does put onscreen is something far more recognisable – namely, the real-time hesitations, ambivalence and emotional loose ends that occur in human interaction. In his movies, he may observe the lives of his inner-city twentysomethings with anthropological rigour, but what happens during filming is also deliberately left open to chance. At a time when most film graduates plot their movies (and their careers) with cold-eyed precision, there is something splendidly perverse in asking an audience to think and react to what they’re seeing, to this extent.” – Gordon Campbell, NZ Listener, 2003

The Films:

Uncomfortable Comfortable (1999)

“The digital [feature film] revolution started [when] Wellington film-maker Campbell Walker debuted his first feature, Uncomfortable Comfortable at the 1999 [NZ] International Film Festival. -Philip Matthews, Senses of Cinema, 2004.

“ ‘Uncomfortable Comfortable’ is really good… The Cocteau dictum states that when every means of visual communication is as easy as using a pencil and a paper, one can express oneself to one’s full potential using anything. I see that Campbell (walker) has really taken it to an extreme and his actors have done likewise” – NZ film pioneer John O’Shea, 1999.

“The film’s faith in its characters allows it to sidestep the comedy of embarrassment into which it could so easily slip, and we end up with something much more satisfying and unexpected. In so completely bypassing the mainstream of New Zealand film,Uncomfortable Comfortable makes brave forays into areas seldom troubled by local filmmakers, and brings back footage that’s worth the risk” – Andrew Langridge, NZ Film Fest 1999.

—

Generally regarded as the first digital feature made in NZ, and something of a cause celebre at the time, we made Uncomfortable from an improvised script developed in workshopping with the actors and then shot over 5 days with increasing infidelity to the original text. In hindsight, a comedy – which we discovered at the first screening when several hundred people laughed in a slow, unwieldy ripple through the movie as they encountered unfamiliar familiarities in the film.

I wanted to take a slow, searching look at a couple in trouble – its not punched up melodrama, just the awkward way two people try and fail to negotiate the realisation that it isn’t really working out. At the time we were working within an explicitly realist mode, somewhere between John Cassavetes and Maurice Pialat, exploring the way that improvisation generates an emotional complexity within the characters while helping to maintain an interestingly curved narrative – CW

Why Can’t I Stop This Uncontrollable Dancing (2003)

“Campbell Walker’s closely observed account of a young woman dealing ambiguously with phone harassment from a former boyfriend, Why Can’t I Stop This Uncontrollable Dancing? is virtually a pas de deux for camera and actress. Nia Robyn, best known for her work in Walker’s previous feature Uncomfortable Comfortable, possesses an uncanny, active intelligence on screen. The play of thought and feeling on her alert, fine-featured face commands the camera in an entirely naturalistic fashion. Here she suggests inner resources to match and reward Walker’s relentless scrutiny. Watching, for example, as she listens, hungover, to a series of drunken messages left the night before, you might feel you share every sensation of her amazement and dismay. “ – Bill Gosden, NZ Film Festival, 2003.

—

A closely observed psychodrama played out in large chunks of real time… A kind of de-dramatised stalker movie building up momentum and compulsion through monomaniacally close attention to the details of a small but disturbing episode in the life of a young woman and an old friend from another town and another time.

Featured in Hamish McDouall’s book 100 Essential New Zealand Films (Awa Press, 2009) – CW

—

“I’m always most interested in making films that are about the way people interact and about the way people can’t interact properly. It would be arrogant indeed to presume that this is something I’m an expert on, and if I was I probably wouldn’t care enough to make a film about it. It’s not as simple or as glib as saying ‘the point is the process’, but to a very large extent, the point is only sufficiently interesting or complex if it is achieved as part of the process, and for that to take place in a film that I make, I usually need not to have a clear idea of how I’m going to get there before I do.

This was especially the case with Dancing. This film was improvised to an almost ridiculous degree – not only did we not plan events. I wouldn’t even let the actors know what they were going to do. They would have to create a whole interaction between themselves with almost no help from me.” — CW, 2003

Little Bits of Light (2005)

“Intimate, acutely observant filmmaking with real emotional power, Campbell Walker’s digital feature bears witness to a young couple’s struggle to survive one partner’s crushing bouts of depression. Alex and Helen are taking a winter break in a rambling old house in the Taranaki countryside. The day may hold distinct and pleasurable ‘little bits of light’, but the nights are hellish and long… Screen acting of such a high order… It’s as if we are watching the private struggle of two people, played out in real time, but sharpened into dramatic focus and suffused with the filmmaker’s love, wonder and dismay” – Bill Gosden, NZ Film Festival, 2005

“With [Little Bits of] Light, a sturdy whisky would be a more appropriate accompaniment than popcorn. While Walker’s films can be difficult to watch for their unrelenting social realism and rough visual style, they highlight one of the most special things about the medium of cinema – the ability of the film-maker to be able to move and challenge us and make us think about our own lives.” – Kiran Dass, NZ Herald, 2005

—

“We spent an alarmingly intense month in the country, drinking lots and getting beaten around by the subject matter. All the rest of the cast and crew tend to look at me as if I’m crazy when I say I had a great time, but making the film has semi-ruined the idea of going back to making films with no money at all. In this kind of low budget but determined film-making, money doesn’t buy you glossy costumes or distracting effects. It buys you time to get things right, time to work with the crew and the actors, time to remove distractions, time to do things again when they’re not right. Having this time is very addictive after you’ve learnt the proper appreciation for what it means; which is learnt by doing it when you don’t have time or money.” – CW (2006)

—

A film about dealing with depression, drawing on my own experiences with then-partner and co-writer Grace C Russell… not as autobiographical a film as has generally been assumed. – CW

Broken Black Lines (2009)

“Walker’s style (along with many of the Aro Valley Digital film-makers) has always been minimalist/realist with largely improvised dialogue (imagine a mixture of Jean Eustache, Chantal Akerman and John Cassavetes) going back to his first short Three Nights and the subsequent feature-films Uncomfortable Comfortable,Why Can’t I Stop This Uncontrollable Dancing and Little Bits of Light. But this new film has something else. The others didn’t necessarily lack this thing – but it is stronger in Broken Black Lines, more refined (which is only to be expected). There is a self-conscious sense of humour which is refreshing in long take, minimalist, improvised cinema. This film is really funny. And the kinds of jokes it makes are both familiar and unexpected. Familiar because the humor could sit comfortably in an episode of Friends or Seinfeld, as well as Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore (collapsing the very real distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ aesthetic assumptions which dominate both mainstream and underground representations of themselves). Unexpected because experimental drama has a habit of taking itself too seriously and collapsing into modernist paradoxes (the realist film which does not realise it is a film is not possible in these times).

Note the subtle shifts of power between the characters (and the characteristically strong female lead – something all Walker’s films possess). Walker’s film revels in the affect-image – in the face (halting action, delaying the relation between cause and effect, opening onto a Deleuzian any-space-whatever). This film makes me feel things. I feel warmth toward the characters – genuine warmth. It is not warmth which is there from the start (engendered by stereotypes) but a warmth which builds as I experience something intimate with them. In Walker’s other films I felt far more like a voyeur, while in this one I feel invited in – as if my presence is necessary to cement the union of the characters. I feel joy at certain moments, happiness at others. It is a film filled with warmth and love. But it is not a film which ignores the pressures of life in order to represent objective happiness – it offers a sense of ‘happiness’ which is fleeting and entirely subjective, negotiated in the moment (without knowing in advance what it is which will make me happy, a non-consumptive happiness).” – Dick Whyte, Hotlink Cinema, 2009

—

“Broken Black Lines was made in Wellington over small bursts between 2007 and now. The budget is in the “negligible” category, probably around NZ$500. We designed it to be a no-budget film that we could make quickly in 2007 when I returned from Auckland to Wellington on holiday. Half of it was shot then, half of it two years later, after what could be described as some fairly dramatic changes in the director’s life.

I’d been living in Auckland, married, and working an office job, which was making me more and more angry and depressed – this is very present in Part 1. We’d been planning a bigger project, working towards looking for funding that didn’t arrive. My friends Elric Kane and Andy Chappell, who were still in Wellington, basically told me I had to come down and make a film with them, so I adapted an idea for a TV series into a La Ronde-style piece that I figured could be made quickly and easily.

Characteristically, when I came down to Wellington to make it, I hadn’t really given anyone a lot of warning of what was going to happen – a quick emailed treatment, a notion for just a couple of the actors, an extreme level of enthusiasm for making a film again, and a parallel level of complete instability on the director’s part…

After shooting the first two parts in 2007 – and another part that I abandoned – I settled down for an extended period of being depressed and not feeling up to completing the film. In 2009, I rewrote the stuff we’d done, in many ways to reflect a slightly more pessimistic worldview that was suddenly appropriate to my life, and with the help of friends shot parts 3 and 4 over 2 days.” – CW (2009)

—

Screenings take place at the Threave Cinematheque, 1/367 High Street, City Rise, Dunedin. Entry by koha, informal or formal conversation with the filmmaker will take place after screenings. Films will start more or less on time.

Mise-en-abîme 1: Ghost Movies: Experimental shorts from the Aro Valley Digital Cinema 1997-2007

Posted in Uncategorized on October 24, 2010 by uncontrollabledancingThese are the programme notes for tonight’s screening at the Frederick Street Light and Sound Exploration Society in Wellington, a retrospective of short experimental films from artists associated with the Aro Valley Digital Cinema curated by myself, and featuring one new film by myself… and one to be discussed later…

The Uncomfortable Film Club presents

Mise-en-abîme

<placing into infinity…an infinite reproduction of a sequence>

< to put into the centre>

A regularly irregular series of screenings based around buried cinemas of expansion and contraction.

First screening 24/10/10

Ghost Movies: Experimental shorts from the Aro Valley digital cinema 1997-2007

Frederick Street Light and Sound Exploration Society

Frederick St

Wellington.

“The future of cinematography belongs to a new race of solitaries who will shoot films by putting their last cent into it and not let themselves be taken in by the material routines of the trade.” -Robert Bresson

The “minimal realist” feature films of the Aro Valley Digital Cinema are now well documented. Less screened and known is a lively parallel/ related scene producing a large amount of similarly singular work in a short experimental vein.

This is a lively, diverse set of work – mostly previously unseen – emphasising strands of adventurous and lateral responses to the notion of a personal cinema of poverty. All produced for essentially zero funding, by set of individualistic stylists sharing an engagement with the idea of manifesting the caméra-stylo in personal ways, these films make use of a variety of techniques and aesthetic perspectives that will surprise those used to the less expressive and varied palettes of the Aro feature films.

The films:

Haircut (Diane McAllen, 2003, 4 mins)

Usually better known as the producing member of the original Gordon Productions collective, McAllens experimental video work from 1996’s Spirit Level to this series of works tends towards explorations of the textural possibilities of the medium in domestic, diaristic modes, or constructing experimental narratives around anxious or depressed female characters – usually played or referred to in the first person.

In both types of work, there’s a strong attention to the textural and lateral possibilities – characteristically of S-VHS – sometimes with ingeniously transparent variations on techniques like stop motion and painted animation.

Haircut features a variation on a frequent McAllen strategy, refilming – in this case a handheld refilming off a TV screen, of a fixed camera aimed at a mirror – behind the artist unsatisfactorily seeking comfort in a new haircut. Needless to say, even repeatedly re-applied makeup isn’t going to bring much comfort through all these screens…

Faded Memories (The tape is not damaged) (Diane McAllen, 2003, 4 mins)

…But everything else is in this aggressive reworking of a failed film about a failed relationship. Again McAllen is utilising the distinctive colour, grain and bleed of S-VHS refilming with other multiple layers of technological obsolescence to construct a bitter and baffling rejoinder to the hopes and aspirations of another of McAllen’s anxious heroines. Oh yeah, and it’s also a stop motion film that never stops… Perhaps the only way to get past all these memories of failure is just to keep glossing past them…?

Firecat (Nia Robyn, as Robyn V, 1997, 2 mins)

Robyn (also Phipps) is probably best known as the superb female lead in the Aro features Uncomfortable Comfortable, Why Can’t I Stop This Uncontrollable Dancing and Little Bits of Light, but was probably the first person involved with the Aro “scene” to actually start making films. Firecat is typical of the experimental poetics of her style: an enraptured study of the textures and shadows in dialectic of flickering flames and a cat jumping from a tree to a rooftop, set to a clattering soundtrack.

Vera (Colin Hodson, 2007, 6 mins)

The first part of Vera is pure visceral/ kinetic sensation, the joy of making films. Director Hodson and collaborator/ subject Vera play small games of hide and seek while spinning the camera around on a rope – No-one will ever lend Hodson a camera again after this! – in the middle of an nocturnal urban atmosphere.

For the second part, we shift to a static interior, a scene and a tone superficially familiar to those who know Hodson as the evasive lead in Shifter, On and Uncomfortable Comfortable. He and Vera are talking in the background, and it sounds like an intimate scene of disconnection from one of those films… Except here the play is with the expectations of the audience, here the characters are articulate and engaged… and the piece functions as a critique of the limitations of the drama of the other films.

“I shot this one evening in late 2005. I wanted to get to know Vera more, and asking her to help me collaborate on a video project was a great way of getting us working together.

The second part of the video is actually a real-time erasing of the second video I wanted her to be in, shot immediately after the first part. For this video, I was wanting to capture non-English speakers talking to me in their native tongue. What I thought would be interesting is that these people would talk to me in a language I do not understand, but, because we have a friendship, there would be some sort of communication anyway – a physical one, demontrated through body language and facial expressions. After I recorded it, Vera was uncomfortable with what I was trying to do. (She states her confusion with my objective in the recording, as you hear). She asked me to erase the recording of her recounting any pets she has had spoken in Ukrainian. So what we see/hear in the second part is the overwriting of the tape, and of course, laying down a new recording in the process.” – Colin Hodson

Smoke (Colin Hodson, 2007, 5 mins)

A striking elegy for a new city about to be lost – more from the fertile series of short works Hodson made in Amsterdam in 2005.

“The video camera in Smoke searches. Looking for someone to connect with. Looking in apartments across the road. Anywhere the lights are on. Nobody’s home. But it’s late 2am. So everyone’s asleep okay. Soon a few people wander by: a passing cyclist or some people at the end of the street, drinking done. But they don’t see me, don’t come close enough.

So the city itself offers me some company then, going about its stillness. Same stuff since medieval times. I’m just one person looking across the roofs late at night, but those roofs have been gazed on for hundreds of years. I can’t feel those gazes, connect to them, but I believe they must have existed. My memory of the city will be big, but the city won’t have noticed me. I’m too small.

The only thing I can see that suggests transience at the same scale as me is the blue wisp of steam curling out of that chimney over there. Smoke/steam. Steady. It keeps me company through the whole filming. And I’m filming cause I’m leaving. An accelerated year brought to a close. So the filmmaking is me hanging on. Trying to catch the feeling of the apartment I had, and the street, and neighbours you can’t see, but were there the whole time. You’ll see them, I caught them in other videos.

The sky glows, clouds fed by the light of the city. Light for who though? More people like me? Cause the light’s bleeding out of the city and bouncing off the clouds but there doesn’t seem to be any consciousness/thought behind those lights. The city’s asleep I mean.

Why the steam? What’s going on in that building? Is someone feeding that fire? Does it know about me too? That smoke, that steam, that’s what I can hang onto. It gives me something.” – Colin Hodson

Terminal (Andrew Chappell, 2004, 15 min)

A stranger who is diminished upon arrival at a dead end is played by free jazz saxophonist Rick Jensen with a stern, distant grace, and filmed with a rigour and patience that typifies the Aro features, combined with visual elegance and measured editing tones all its own by Andrew Chappell in this terse study of the tenuous gap between solitary self-possession and desolate loneliness. The emptiness of the city is the key motif here, in a film wholly attuned to the alienating rhythms Wellington can use to welcome visitors.

Chappell’s debut short – he works as a cinematographer both in film industry and on Aro films – famously made lousy genre filmmaker Greg Page say he felt like killing himself during it, a promise he should have been forcibly encouraged to keep. Any attuned audience will find it immediate and mesmerising.

Girl Yawning (Elric Kane, 2004, 6 mins)

Currently resident in L.A., but self identifying as an Aro filmmaker, Kane is probably best known for his feature collaborations with fellow U.S. resident/ lifelong friend Alexander Greenhough (Kissy Kissy, Murmurs, I Think I’m Going). On his own, though, he’s made a rich array of short experimental pieces, many like this one on Pixelvision.

Shot during a period of isolation in 2004, we’re again looking through the alienating effect of multiple frames, as the already garbled nature of online chat room videos is further visually degenerated and fragmented by Pixelvision… The attempted palliative of various and anonymous human contact thus becomes an even deeper, smaller isolation in between the requisite codes and gestures.

Live cinema. Soundtrack composed by Elric Kane and performed by Haulout Seal Orchestra.

Bardo Follies 2 – Burn Baby Burn (Dick Whyte, 10 mins, 2006)

Dick Whyte is definitively the most prolific of the Aro Valley digital filmmakers…

Since the late 90s he’s produced a dizzying amount of experimental film work, much of which remains unseen – although his most recent work is usually produced for and released online (see http://www.wayfarergallery.net/artdick/ ). He’s also a theorist, poet, writer, musician and painter – among other things.

“This is a sequel (NOT a remake) to Owen Land/George Landow’s classic avant-garde film “Bardo Follies” using an old 16mm projector (thanks Alex) and some film originally from the New Zealand Film Unit (thanks Toby and Melissa). Although the images are projected on 16mm, the film was made digitally by filming the wall.

I was interested in the idea of making sequels to avant-garde films to question the avant-garde’s reliance on the ideology of the “new.” In a postmodern world (where “everything has been done”) how can the avant-garde operate successfully? And why is the avant-garde classically afraid of revisiting ideas?” – Dick Whyte.

Live cinema performed by Dick Whyte.

Curator’s response:

A cinema retrospective is always an interaction with ghosts. With this one, even more so: themes of isolation, disconnection abound, ghosts of relationships, memories, failures bleed through all these works… The same thing is visually expressed through the play with multiple frames and low resolution formats breaking down the image resolution, accuracy, manifestation… and the singular and personal approaches constitute a kind of “ghost genre”, made in ways that are shadows of the traditional film-making apparatus, approximated responses to cinema history well and truly separated from the main lines – left to germinate, then break down in a quiet cul de sac suburb off the side of a small, self-deceiving city of bureaucrats and middle people…

But from here I like some of my ghosts, I don’t want to exorcise them all, they keep me company in my small house. The reason for bringing all these ghosts back tonight is to come to terms with them – to claim a place for them in the world. Isn’t that what a ghost really wants? To validate the death? Otherwise they can get too close.

But any time spent in such a town of damnation – that is, any town anywhere, for an underground artist – usually involves, by necessity, avoiding a too intimate contact…of course it’s not always as simple as that. So, to keep moving, walking around the streets in solitude, listening to the music of the place, is just a normal practice… but they’ll always catch up with you again.

Being alone and intimate with a ghost can provide for an uncertain relationship to solitude. Ghosts aren’t predictable, they don’t manifest in accordance with the laws of physics… Instead they switch on and off, dart from time to time, or place to place. Their physicality is not made manifest but remains perceptible, and obviously…. haunting…

You can’t ever quite capture and contain them, but the process of trying to do so can create something else just as meaningful, impactful. Hopefully.

With this is mind, here are two very different new films that constitute a curatorial response to this programme:

Town of Damnation

AABCD (Both Campbell Walker, 2010)

Mise en Abyme is curated by Campbell Walker, who wrote the notes unless otherwise credited. He can be contacted at uncontrollabledancing@gmail.com, and these notes will be available on his film blog, http://www.sealinthesea.wordpress.com

Thanks to all the filmmakers, Daniel Beban and Sally Ann McIntyre.

Links:

There is an Aro Valley digital group on vimeo: http://www.vimeo.com/groups/arovalleydigital

Dick Whyte’s work can be found at http://www.wayfarergallery.net/artdick/

and at http://recons.tumblr.com/

Colin Hodson is at http://www.colinhodson.net

Three Nights (1997)

Posted in Releases on October 11, 2010 by uncontrollabledancingCourtesy of fellow Aro Valley filmmaker Elric Kane, online now is the first film I directed, Three Nights, made in 1997…

[Sadly I’ve had to take this link down for the time being]

When we made it, I had this idea about making a long film about the end of a relationship, and I wanted to develop it with actors, using a lot of improvisation, and a minimal, long take approach. I’d met Colin Hodson in the Victoria University of Wellington film classes we were both taking – he’d recently come back from a period in New York where he’d been working with people like the Wooster Group and Richard Foreman, and I think he was open to something a little more engaged with something new than he was seeing in Wellington’s fairly conservative theatre scene of the time – let alone the even more reserved film scene. We’d talked about music more than anything, and he was into doing something improvised.

The actress Zoe had been in my then partner Diane McAllen’s experimental short Spirit Level (1996), so we knew her a bit, and she seemed interested then too – although not so much of an extremist in perspective, I think she liked the idea of working within improvisation as well.

So, part of my notion was to create a fictional failing relationship by workshopping and documenting different parts of how the relationship progressed. We had a couple of sessions at Zoe’s house in Newtown – the first time I just filmed them talking to each other, interacting as themselves, the second time, we decided to have a go at pulling together the way they “started out”, or “first got together”.

I really can’t remember if we’d written anything down at all about it, I think there was some plan discussed, but not too much of one. We shot the bedroom scene – there was some action before that, that I didn’t keep, but once it got to the scene that’s intact now, I knew that, firstly I should just keep rolling, and see how long it took Zoe and Colin to exhaust the possibilities… and then soon after, that these weren’t necessarily possibilities they were going to exhaust in a hurry, as long as they were free to respond in the ways they did.

So – this moment seems critical to my early practice now – the idea that the best way to get a good performance from an actor, was to allow them to be as close to a person as possible…

And the best way to do that was often to provide an environment where they could do that… and to trust the actor you chose to come up with a lot of the details of their character on their own. At this stage the easiest way to do that seemed to be to allow them to be as close to themselves as possible… And of all the films I made, Three Nights is probably the one that contains the least constructed performances – but they are still performances too, full of choices and variations, happening all the time – as always occurs in an improvised and open environment.

We all felt a bit excited after the night’s shoot – it felt like we were onto something! There was a student video awards at Vic coming up, so we decided to try and turn our night’s work into a short about the start of a relationship. After Diane and I did a paper edit, we went into Zoe’s partner Jake’s office and edited it from camera onto the S-VHS deck sitting there in about 2 or 3 hours. And, film made – I don’t think we spent much money at all on it, beyond an S-VHS tape for the master to complete on.

When we showed it at the student video things, it was pretty much ignored in favour of the usual hack-in-training dreck that works at such events… But hey we liked it, and as was the style of the times, showed it at the 1998 Fringe Film Fest [a phenomenon of the 90s, that used to be a serious place you could show and talk to people engaged in making films before it got ruined by middlebrow industry producers who hated to hide their scorn for people making work they couldn’t understand and about which I can get really steamed up if you want to hear it]. We got a good evening slot, and a big crowd for our session… and here, people liked it! People laughed and responded, people liked the performances, the tone, the directness of it.

However one person who’d not found it a completely positive experience was actress Zoe. After seeing it, she decided she wasn’t up for doing a whole big film in this way… So we Diane, Colin and I regrouped, rethought, showed a few people this little short – one of them was Vic film lecturer/ historian Russell Campbell, who earlier that year had not let me into his Film Production course, which had been running at the same time as we were shooting. Russell later coined the notion of the Aro Valley group, and has been one of the main commentators on it.

In fact I insisted Russell let me show the film after class one day, and also watching was a filmmaker who had gotten into the course, Robyn Venables. She expressed a keenness for the film and in “working with Colin”, so she became our new lead actor… And remained an increasingly confident lead actor for the 3 first features I made, the second two as Nia Robyn. As she recalls:

“I freaking love this film. I remember the day I saw it. It was at the end of film crit class and it was the first day i really liked you CW. Before that you were that slightly annoying guy with the encyclopaedic knowledge of film that always dominated the class…”

Watching the film now… I notice a couple things I find interesting. One is the intrinsically New Zealand nature of these characters – All the films I’ve made have been about the way relationships function in NZ culture, and this is quite aggressively so… In ways that I’ve always been somewhat uncomfortable about. I would then have feel very uncertain writing a character who says the things that Zoe does in the film about sexual politics, but they do seem very much in line with women I have known, and the way in which they are awkwardly articulated is even more so…

The other thing I notice is how aggressively unpolished it is! Obviously shot in one night, obviously artificial in structure, there is no effort to disguise the minimal nature of it, you can hear me snickering, hear the power cable banging on the floor, the reframings are rough as hell and not cut out, they’re wearing the same clothes for every night of it – But it partly works because of that – I’m in hindsight, really pleased to think this is the first film I made. It feels like all the attention was put into getting the right things right, and none whatsoever to anything else – and more, for the angry young “enfant terrible of NZ filmmaking” I started getting lazily tagged as later on – all the choices were the opposite of the ones people were making in the NZ films around us at the time, all so concerned with physical craft, process invisibility and script structure…

Drones for Marina 3

Posted in Uncategorized on October 1, 2010 by uncontrollabledancingvimeo=http://www.vimeo.com/15432418

Another film in the Drones series of experimental shorts.

This one is called Drones For Marina 3: Rethinking A Glib Gesture (an autofictional documentary).

In related news, there is now an Aro Valley Digital vimeo group at http://www.vimeo.com/groups/arovalleydigital.

Lots of work there – everything from here of course, but also film by Dick Whyte (who’s set the group up) and Elric Kane up already – including Elric’s insider feature doco on the Aro Valley digital movement, Campbell Walker is a Friend of Mine.

“Scenes from the Aro Valley, Paramount, April 20-23 2006”-

Posted in Uncategorized on September 23, 2010 by uncontrollabledancingThese are the original liner notes for the 2006 “mini retrospective of the Aro Valley DV film movement 1999-2006” curated and written by myself… The first time we the filmmakers referred to the existence of the group that could be seen as including our work. I’m putting it up as a time capsule in a way – there are many ironies and misapprehensions involved, but it has a historical meaning I’d like to have noted, preserved.

Scenes from the Aro Valley

A Mini retrospective of the Aro Valley DV film movement 1999-2006

Shifter

2000, Directed by Colin Hodson

“Shifter’s life is a mess. His flatmates play “horrible un-music” and drink all the milk. He can’t talk to his ex without arguing. He can’t get his answerphone messages. His new flat is a tip, and he’s having nightmares about killer rabbits – but it gets worse…”

– Gordon Productions original description.

“As the events accrue, and our eponymous, engaging and elusive lead lives several days in his ordinary/ extraordinary life, one’s initial listlessness gives way to a perverse fascination – as the slightest event, be it an odd dream or the spilling of a cup of coffee, takes on epic proportions. What emerges is an endless loop of unlocatable anxiety, as Shifter’s interactions with his ex-girlfriend, new neighbour and a girl he tried to picks up in a bar, all fail to explain his ontological discomfort; his quest, in this way, becomes universal. A self-contained slice of in medias res existence, Shifter captures the spaces in between with unpolished exactitude.

Wholly improvised over several days and produced for a grand total of $110.00, Shifter is the closest that film gets to real life, and shows that the alienated cinema of the Pacific Rim stretches as far south as New Zealand.”

– (Mark Peranson) Vancouver Film Festival 2002

Shifter was a strange film to make. It was really cheap and weirdly ad hoc and its one of my favourites of the Aro Valley films. I shot it, except for the scenes I’m in, and Diane McAllen recorded the sound, except for the scenes she’s in. She’s in a lot of scenes – Whitey, the character she plays was supposed to by played by Richard Whyte who couldn’t make it – so for those scenes I was walking around the house holding the camera in one hand and the boom in the other.

After his disturbingly convincing turns at emotional evasion in this and Uncomfortable Comfortable before, Colin was starting to get people not really wanting to talk to him so much any more. We got this a lot with these films – some of these performances were sufficiently good that people didn’t really want to believe that a bunch of unauthorised filmmakers with no money could have acheived them, so they tended to assume the actors were just playing themselves. (CW)

Preceded by

Terminal

2005, Andy Chappell

A very different version on a similar theme to Shifter from Andy Chappell, and a clear inheritor of some similar perspectives to the “Aro Valley Movement”. Always very strongly visually motivated, Andy is finishing his second short slowly now, a sci-fi film featuring Rob Jerram from Little Bits of Light, with a shaved head for the role. (CW)

Murmurs

2003, Elric Kane and Alexander Greenhough

“Life in a Mt Victoria flat is observed with sly wit by Elric Kane and Alexander Greenhough in their second no-budget digital feature” – Bill Gosden, NZ Film Festival.

“If for nothing else, this film is recommended purely for being made by two former Victoria University film students, who are showing the rest of us wannabe filmmakers how to make compelling and interesting films without any money.

There is also the fact that it is set in Wellington, and unlike some other films that use cities as a form of name-dropping, the city becomes an integral part in the alienation and darkness of the film. For example who’d have thought the Overbridge could be made into a sinister and cold place?

The film can also be recommended because it’s set in a Mt Victoria flat with characters and situations that most students and most other people can relate to.

However, it is also recommended simply because it is a really good film.”

-Branavan Gnanalingam, Salient

I’d helped out (at times negligibly) with Alex and Elric’s first feature, I Think I’m Going, and soon after it was finished, they launched straight into Murmurs. Apparently they were wanting to sneakily make another film to surprise us all with. These boys often have real issues with screening their work, fine though it is, and I’m still kinda surprised that they were both keen on screening it here. Murmurs is thematically very close to Shifter, and in filmmaking style and personal philosophy a complete opposite. Please note that neither of these films are relationship movies – something else the Aro Valley filmmakers have always been accused of making.

Look out for a steely cameo by George Rose, who’s really the original independent no-budget Aro Valley fimmaker since the 70s when his radical first film Artman first raised socio-political hackles that none of the current generation have had the balls to try and interface. Also note the no-budget-est spin on that “de Niro in Raging Bull ridiculous weight gain” thing, in the otherwise svelte Kristin Smith’s pretty stellar inhabiting of the decidedly un-svelte Amy. (CW)

Preceded by

Experimental Shorts

2001-2004 directed by Richard Whyte

Featuring 5 films: BROOKLYN, Lightbulb, EARth, Lunar, Storm

Five experimental shorts in about 7 minutes by Richard Whyte, among other things a ghost in the margins of almost all the Aro Valley films, and possibly the least known and most active filmmaker involved with the movement. Still lives in the Valley too, unlike the rest of us; next door to the flat Shifter moves into. (CW)

Little Bits of Light

2005, Campbell Walker

“Intimate and acutely observant filmmaking with real emotional power, Campbell Walker’s digital feature bears witness to a young couple’s struggle to survive one partner’s crushing bout of depression. Alex and Helen are taking a winter break in a rambling old house in the Taranaki countryside… Nia Robin elucidates Helen’s anguish and her arresting off-kilter liveliness with unstinting clarity. Happiness is as sharply evoked in the film as the opposite and Alex and Helen charm each other – and us – with some of the knowing playfulness of a French new wave couple.

In this, as in her distress, Robin has her match in Rob Jerram, who plays Alex without a hint of self-serving nobility. Screen acting of such a high order might almost be considered the purpose of Walker’s filmmaking. It’s as if we are watching the private struggle of two people, played out in real time, but sharpened into dramatic focus and suffused with the filmmaker’s love, wonder and dismay”

-Bill Gosden, NZ Film Festival

Little Bits of Light is the most expensive of the Aro Valley films to date, and was filmed in the Taranaki, which’s not really in the Aro Valley.

It’s based roughly on my relationship with with co-writer Grace C. Russell and the improvised into new life with the actors. A glib but sadly rather accurate description of how this film’s affected Grace’s and my life would be to say that, to a large extent making the film helped cure her depression… and gave it to me instead.

We spent an alarmingly intense month in the country, drinking lots and getting beaten around by the subject matter. All the rest of the cast and crew tend to look at me as if I’m crazy when I say I had a great time, but making the film has semi-ruined the idea of going back to making films with no money at all. In the kind of low budget but determined film-making that we’re playing at at this festival, money doesn’t buy you glossy costumes or distracting effects. It buys you time to get things right, time to work with the crew and the actors, time to remove distractions, time to do things again when they’re not right. Having this time is very addictive after you’ve learnt the proper appreciation for what it means; which is learnt by doing it when you don’t have time or money.

All four of the feature film directors represented here are moving into the slightly more arrested, less independent stage of finding that the projects they want to make need more time, and wondering where the hell they can find the money to buy the time with. So this maybe means the “Aro Valley DV movement” is finished. But then again with newer film makers like Andy Chappell moving inexorably towards long-form work, maybe it just means it’ll be taken over by different people. (CW)

preceded by

Other

2002, Diane McAllen

A short animated doco, about what happens when your partner leaves you for someone else. Diane, as among other things the producer/ co-producer of Uncomfortable Comfortable, Shifter, Off and Why Can’t I Stop This Uncontrollable Dancing and one third of the Gordon Productions collective that made these 3 films, was one of the most key people in the early days of the movement. I was the partner that left. (CW)

ALL SCREENINGS WILL ALMOST CERTAINLY HAVE AT LEAST SOME OF THE FILMMAKERS PRESENT.

Also on Saturday night after the screening of Little Bits of Light will be a party to celebrate or bemoan the leaving town of director Campbell Walker and co-writer Grace C. Russell who are moving to Auckland. Actually its also their varioys birthdays, as well as the birthdays of Murmurs directors Alex and Elric too. Please come if you would like to, starts at 10, 10.30. There will be no Q&A after the Saturday night screening but some provision will hopefully be made for those attempting to transition from Little Bits of Light to a party mode that is admittedly somewhat at odds with the film.

Scenes from The Aro Valley was curated and disorganised by Campbell Walker and then hopefully resolved or rescued by Mhairead Connor, Elric Kane, Grace C. Russell and Colin Hodson. The slightly odd program notes were written by Campbell Walker unless otherwise attributed. Thanks to Kate Larkindale and the Paramount, and all the fimmakers involved. In a wider sense, thanks to Bill Gosden and the New Zealand Film Festival for the kind of ongoing support that, among other things, means we have a (sometimes contentious) movement to group our films under.

Since The Accident

Posted in "other", News on September 1, 2010 by uncontrollabledancingMore changes in film funding in New Zealand, more marginalisation of different kinds of work – The Creative New Zealand Independent Filmmakers Fund, an obviously ignominious failure, dying after 2 rounds when the Film Commission decided it could better contribute to screen culture by not funding films engaged in anything beyond the most mainstream of notions… Fair play to them, I guess, they’ve never made particularly engaged or credible claims to care about things outside their narrow range.

Of course it does mean access to funding “experimental” film has pretty much now rolled into a bigger pool with the news that next year the IFF will be replaced by a broader “Media Arts” category… Very ominous news to lose a separate film fund that is engaged with work of substance and quality.

But we don’t really have a film culture in New Zealand beyond the efforts of a few heroic individuals – people like Martin Rumsby, Lawrence McDonald and Mark Williams come to mind in ways that, say, Auckland’s MIC doesn’t. We do have a few filmmakers who battle on to find and raise their own voices despite the culture of mediocrity and concensus – we just lost one who died at her peak in Kathy Dudding, both a filmmaking comrade and a rare active enthusiast for other people’s work. But for all of us involved in non-industrial filmmaking, the roads are just getting harder and harder.

But hey, on the other hand, I just came out of a big black hole… I am now formally stating that I am Not Depressed Any More after being pretty much missing in action, findable in the bar, for the last three years after failure to deal with destroying my marriage. I am now ready to Return To Work, even if work isn’t ready for me – if the above didn’t cue you in, I am among the unfunded by the IFF and finally ready to talk about it without getting pissed of.

This was a bit unfortunate, I decided – I had an application in for a film I think I’m now really ready to make, and make how it should be made. I’m going to post the Treatment and Director’s Notes here, and I’m interested in responses anyone has – but I also think I need to find ways to make it, so if anybody has any constructive suggestions or interest in assisting let me know either here or via email uncontrollabledancing @gmail.

I’ve been working on this for a while – yeah, its a personal project but no its not my life before you ask… It’s ready to get started on. The way I work means intense bursts of activity, especially with the actors, and a certain lack of filmmaking apparatus. I’m going to be hating asking people to work on it for no money when its such an intense – even destructive – project that requires commitments of time and emotion, and that will leave all involved shattered by the end – but ask I will, and can promise actors especially that working on it will be (a) unlike any film they will make with anyone else, especially not in New Zealand, and (b) Almost certainly the best acting they will ever get to do… If they can find a way to give full commitment.

Who else is involved? There are people who are keen, but they may not be able to do it for the money I can track down. At this stage its just me… and I can make a devastating film with this material with a few actors and a crew of 1, though I’d kinda prefer not to. But any resources I can muster will be put towards intensifying the characters, enhancing the ability of the actors to be where they need to be, not in making it more palatable for casual viewers… It’s not that hard to find the shots and sound recording you need if you get that right…

Here’s the treatment, and the Director’s notes:

Since The Accident – Treatment

1

Its just at the end of the relationship – that moment where everything is poised before both Jasmine and Stirling take their last plunge into agreeing that it’s over. They think hard, they look at each with a tired respect, they’re going to do it properly, with love and respect and care…

“Are we finished?”

“Yes we are”

They hold each other for a moment, strong, secure and resolved and then the movie starts and we get to watch it all fall over, violently and messily.

2

Stirling comes up to the door. He knocks, waits a moment, then lets himself in with the key from a boot.

There’s a couple of boxes in the lounge, he picks them up and carries them through to by the door. He goes into the kitchen, looks in a high cupboard. There’s a whisky bottle there. He pours himself a glass, goes through into the lounge, starts flicking through the records. He spots one a little way in, grunts unappreciatively, puts it on the turntable, where it plays quietly. As it plays, he keeps flicking through. Sporadically he’ll pull out another one, forming a small pile. He goes over to the CDs on a shelf and does the same, taking small sips of whisky as he does so. He goes into the bedroom, looking in the wardrobe, the bookshelves as he goes. The house is messy, not dirty, but things are not put away very well. He goes into the bathroom, the kitchen, picking up the odd little thing, forming a little pile with the records in front of the stereo.

Later he picks up the phone – the landline – and calls a number.

3

We cut to Jasmine. She’s walking down a corridor in a large, anonymous building, with a guy, Matt, when her phone rings. She looks at the front of it, and is surprised by what she sees – “Hang on a minute” – and she ducks through a glass door, answering it. An initially tentative greeting is followed by a small explosion: “What the the fuck are you doing? Its not your house any more!”

It’s Stirling, of course, taken aback.

“What do you think I’m doing? I’m collecting my stuff? It’s not my fault you’re not here.”

“How did you get in?”

“The key, in the boot, of course”

“Well, get your boxes and get out again, would you”

Full of self-righteousness, she paces quickly away from the bemused Matt, round the corner, down the steps, walking furiously, loudly as she talks.

Stirling seems to want to talk about which records he wants today, but she’s pretty clear that now’s not the time. He’s chatty but feeding off her aggression, wants to know what the rush is.

“Are you out with someone?” he asks, teasing her when she denies it. She loses her temper, hangs up on him, turns her phone off afterwards, then realises she has no idea where in the building she is, or where this guy Matt might be. She wanders, lost, turning corners blindly until she comes to an exit, then walks out onto the street, looking up at a large apartment building towering over her, sits, waits.

Eventually a concerned looking Matt comes out, and they go in.

4

Inside Matt’s house – He’s older than her, and seems nice enough, but the conversation isn’t really flowing, and she’s still embarrassed about getting lost in his building. Eventually she kind of throws herself on him awkwardly. He seems happy enough about this, but it’s hardly an edifying encounter – she can’t really deal with it when he kisses her or touches her, lies there awkwardly when he tries to go down on her, but won’t acknowledge that there’s anything wrong. It’s like she shouldn’t be allowed to have a good time, so she won’t.

5

Eventually she goes home. The boxes are gone, and so is Stirling’s pile of records. She sits on her bed hugging herself. She didn’t think it would be this hard, but whatever punishment is in store she’s up for it. She probably deserves it, she thinks.

6

Stirling is staying at his parent’s house, but they don’t seem to live there at the moment. At the moment he’s in their big, tastefully appointed master bedroom. He’s put away all the things in there that look like they might belong to an older couple, so it looks a bit like a hotel, anonymous. He’s going to be using it as his seduction room, and he’s got Lydia in there with him now.

She’s a young, normal woman, blond, professional, well turned out, drunk. Stirling is a bit drunk too. He’s currently fucking her from behind. He isn’t showing a lot of affection, keeping her at some distance as he fucks her. When he’s about to come, he pulls out and does it into the sheets as she collapses face forward onto the bed. There’s not a lot of eye contact going on.

7

A few minutes later Stirling is in the bathroom, angsting out a little. He’s staring at himself in the mirror, not really in a narcissistic sort of way. As we watch, he starts to move his head back and forth towards the mirror, getting closer and closer to it with each swing until he starts to bang his forehead against the mirror, gently, but with an implied promise of force to come.

The door opens behind him, and Lydia wanders in naked, and goes over to the toilet, sits down, has a piss.

“You look drunk”, she says to him, currently resting his head still against the mirror.

She finishes, washes her hands. As she dries them, she scrutinises him a little.

“Are you ok?”

We look closely at Stirling’s face up against the mirror. He’s not moving now, eyes shut, thinking hard. After a long pause he speaks, quietly, deliberately.

“No, I’m not alright, I’m not alright, I think I need help. Will you help me Lydia?”

He turns to her. She’s long gone.

He sways a bit, laughs in self-disgust, breathes a sigh.

8

Stirling looks round the door into his parent’s bedroom. Lydia has gone to sleep in there. He walks down the hall to his small childhood bedroom, still with its small single bed, childhood accoutrements, and goes to sleep in his own bed.

9

It’s the next morning, and Lydia is waking Stirling up with a cup of coffee. She’s talking freely.

“I wondered where you’d gone – this room is cool, who usually lives here? I thought I’d make some coffee for us, but I gotta run, gotta get home and get my work clothes on or I’ll be late….”

He blurrily sits up as she continues. She looks clean, made up, fully in organised morning mode. He’s a little repulsed by this vision of young health. She gives him a quick kiss on the cheek as she leaves. She firmly but gently says “Thanks for having me, but I don’t know that we need to exchange numbers or anything, do we?”

10

Jasmine is sitting on the floor in her bedroom, just at the point of giving up on the comprehensive re-organisation it needs to become properly hers. She’s surrounded by posters, books not on their shelves, cupboards in search of new corners, but she’s had enough of trying to claim back the flat. It’s time to go out again.

11

Stirling is sitting on the little single bed in his bedroom, although he too looks to be in transitory mode – there’s an open clothes bag sitting on the floor. He’s taking refuge in old pleasures of home, reading an old adventure story from his childhood, smoking a cigarette carefully out the window like a teenager.

12

A barman is leaning over a groggy Jasmine curled up in the corner of an empty bar. He’s telling her she can’t sleep here, she’ll have to leave.

13

Jasmine is walking the streets. It’s late, they’re deserted and she’s thoroughly momentum free, shakily and haphazardly putting one foot in front of another.

14

Now it’s getting towards dawn, and she’s sitting hunched up in the corner of a bus shelter. A young guy on his way home. James, comes up to her, shakes her a little

“Are you alright?”

She latches onto him as the final saviour for a wasted night.

15

She’s gone home with him, and now she’s awake, still drunk, quite manic. She tries to do a little dance for him, starts to take off her clothes. He is excited, but wants to talk, so he sits her down, makes her a cup of tea, makes her laugh and relax a little. She tells him a little about what’s been happening, and looks glad of someone to talk to about it.

As she starts to approach a quieter level of equilibrium, he reaches in to kiss her. She responds quietly but with warmth. When he excuses himself to go to the bathroom, she makes a joke about not wanting him to leave, smiles at him again, gets a small kiss as reward then does a runner as soon as his back is turned.

16

Jasmine is getting ready to go out for another evening. She’s dressed up, trying to look just a little tarty, and has her hair done. She’s in the bathroom putting on her make up carefully, controlling exactly how she looks. She sits on the toilet, and pulls down her skirt, worries away at a red, sore ingrown hair with tweezers, then gives up, slathering it with makeup concealer. It doesn’t help much.

17

Stirling is also preparing himself. He takes a lot of time and care over it too, ironing, moisturising, shaving. He jerks off for a while, not to come but to get himself a bit revved up for going out. He dresses carefully in his going out clothes, before heading out.

18

Stirling is talking to Katja, an old friend of his from years ago. He’s telling her about the break-up, and she’s making the kind of supportive noises you expect of your friends, especially the ones about how awful Jasmine is and how angry and worried Katja feels on his behalf. He’s friendlier and warmer than we’re used to seeing him, and opens up moderately – though we can still sense wariness. Katja is obviously fairly keen on him

19

Later they’re in bed. They’ve obviously just fucked, and Stirling is looking restless and distant like he usually does when expected to show some kind of affection. Katja is trying to kiss him, snuggle up to him, and he’s trying to quietly get her to settle for sitting still.

She’s concerned – “What’s the matter?”

He denies anything is wrong, wriggling further along towards the edge of the bed.

She persists – did she do something wrong, is he upset abut something?

Eventually, under duress, he admits he maybe feels like he shouldn’t have done that, he doesn’t feel very proud of it, that he should have held back… It was nice and everything, but…

She looks levelly at him, at his earnest expression.

“Oh god,” she says. “You thought you were giving me the pity fuck.”

20

Jasmine is at home, putting books back onto the bookshelf. It’s the last part of reorganising her bedroom. She takes her time ordering them. They don’t take up more than two thirds of the shelf, so she turns some around so they’re facing out. She stand up and looks around – the job is done. She looks pleased for a moment, and then it drifts off her face.

21

That night, Jasmine is standing at a bar, vaguely watching a band carry their gear off when Stirling comes up behind her. They’re pleased, and not awfully surprised to see each other. Stirling goes to hug her, and she pulls away, but says she’s pleased to see him anyway.

A little later, they’re standing together, watching the main band playing. They look like a couple, really, although there’s a weird tentativeness at times.

22

Its pretty late by the time they both get back to Jasmine’s house, and they’re both pretty drunk. We’re seeing a different side to them here – they’re affectionate, relaxed, obviously taking pleasure talking to each other, being with each other.

The bottle of whisky Stirling was drinking earlier in the film comes out, and they put on a record and curl up on the couch. They talk a little now about which records they each want to get from when they were together, and they talk about the band tonight, and when they last saw them –

“Do you remember, we were doing a really drunken kinda waltz up the front?”, she says

“Ah, vaguely. I seem to recall them being quite surprised about it. They probably don’t get a lot of waltzing at their shows”

“No there was none tonight”

Later she says

“I should have expected you’d be there – but if I’d known, I might not have gone”

“Really? You trying to avoid me?”

“Of course I am, its easier that way”

“Oh. Ok.”

He’s a little nonplussed.

“No. Its ok, I’m glad to see you after all. I think I must be missing you a bit.”

It’s almost as if its Christmas in the trenches and a truce has been called between them – they toast each other, dance to old records, talk about past times. good and bad. For a while they’re having what seems to be a pretty good time between two people who know each other really well – better than anyone else – and who’ve both been starved of someone to have a good time with.

But, it slowly slips in that the converse is true as well – they are both fully aware of each other’s weaknesses, and by no means incapable of exploiting them. As they get closer physically, they start to increasingly dig at each other in the way that only a couple who’ve lived together for ages can.

“Hey, stop grabbing at me -”

“You used to like it”

“No, I just used to like being wanted. Maybe I’ve grown out of it now. Maybe you were just never very good at it”

23

Soon after they’re fucking, but not well. Their bodies don’t seem to fit together any more, and Jasmine starts to withdraw from responding.

Feeling this, eventually Stirling loses his hard-on. He sits on the edge of the bed, and they both look away, feeling the weight of recent events.

He reaches out to her, trying to recapture the warmth and affection of earlier in the evening. He wants to stay, not for sex, just for closeness. He tries to lie next to her and hold her, but she pulls away, turns around towards the wall.

“Just go away,” she says. “Leave me alone”

“But I miss you, and you miss me too – what’s wrong with just holding you? Please?”

He tries to hold her from behind. She pushes his hands away and they struggle a little.

“I don’t want to”

“But why not?”

“Because you make me feel sick. Because I don’t want you to touch me”

He pauses, shaken, and lies still, next to her, not quite touching, almost winded. There’s a lengthy silence, then he sighs and gets up. He puts on his clothes without saying anything else, then stands up and stares at her. She’s staring fiercely away from him at the wall, curled up tightly. We hear him walk down the hall. She doesn’t move until she hears the door shut, when she finally relaxes her body – she was scared, but she coped with it.

She realises she’s shivering. She gets up and goes into the bathroom, feeling ill. After kneeling over the toilet bowl for what seems like a silent eternity, she sits back up.

24

Stirling is wrapped up in the duvet at his house, in front of the TV, eating instant noodles. He’s expressionlessly watching the sex ads they play after normal programmes have finished. He looks exhausted, completely emptied out.

25

In the late afternoon, Jasmine is walking home from her office job. She runs into Betty, a cool girl she knows a little and likes a lot. They get to talking about gigs and people and clothes.

26

Jasmine ends up at Betty’s house to drink tea and listen to music. They sit in Betty’s room and try out her clothes and make up. Jasmine is initially a little shy and wary, but she soon relaxes and starts to have fun. For the first time we see her trying to make a friend – she’s been so alienated from everybody, between being with Stirling and then being without him, she’s forgotten the simple pleasures of making a new friend.

Only she’s going about it in an odd way. She’s talking freely and happily to Betty about her life – but from what we can tell, she’s mostly lying about it, tentatively at first, and then more brazenly. She’s having a fine time, much more relaxed than we usually see her – it’s just pretty much all fictional.

27

Across town, Stirling is in someone’s bedroom with some girl at some party. They’re both drunk and aggressive, wrestling with each other and their clothes, enjoying pushing each other around and being pushed back. He pushes her face first against the wall; she pushes him back onto the bed and sits astride him. He pushes her off again, and reaches for his jacket. He takes out a cigarette, lights it, and puts it in her mouth, telling her to smoke it while he fucks her. When she refuses and stubs out the cigarette, he tells her to turn around. She laughs at him and complies, and they start fucking vigourously.

The door opens and a man comes into the room. It’s his room, and he’s surprised to find people in there, although he initially seems more upset that they’ve been smoking in there. When he tells them to leave, Stirling loses his temper and jumps the guy, knocking him off balance. He sits on top of him and slams his head into the floor. The girl attempts to stop him, and he elbows her away, then looks up, leaps up and runs out.

28

A little way down the road, he’s walking hard, breathing heavy, somewhat shocked and manic, He just wants to get home and under cover before he does anything else that bad.

29

Jasmine is at a different party. It’s really late and the party is running down. She’s leaning drunkenly over a cute boy, Logan. She feels pleased with herself – he’s a good 4am score, and a couple of slumped girls look grumpy as they leave.

30

Back at her house, she pulls him into the bedroom and onto the bed. He lies down across from her and pulls up her shirt, blowing raspberries on her stomach. She puts on a CD and goes to the bathroom. While she’s gone, Logan looks around the room. He goes through the drawers and the CDs.

When she comes back, they snuggle back down onto the bed. He gets up to take off his clothes at the foot of the bed, making a little show of it. She’s amused. He comes back up to try and take off her clothes, but she wants him to slow down, and to kiss him.

When he has taken her clothes off, she slides down to go down on him. He sits watching her. After a couple of minutes he stops her and takes out a condom – “Are we going to do this?” She teases him a bit; she’s enjoying herself, then puts on the condom. They have good, fun missionary position sex.

Afterwards, Jasmine is tired and is falling asleep very quickly. He keeps talking to her for a while before he realises she’s gone to sleep. She looks relaxed.

31

It’s the early evening. Stirling is moving through his place, collecting up the dishes he’s left in various rooms, and taking them to the kitchen. Some of them have been there a few days. A little later he’s washing them. He’s a meticulous, patient dishwasher, and he spins the task out as long as he can. Its almost as if he doesn’t have anything better to do.

32

Meanwhile, Jasmine is sitting in her lounge, going through her clothes, sorting through them, putting them into two piles. When she’s done, she picks up the bigger pile, and takes them back into her room and dumps them on the bed. She takes the smaller pile, puts them into a plastic bag, and puts them next to three boxes piled in the hall by the door. She’s working with a quiet but sustained energy.

33

It’s late again. Stirling is back at his place with Rebecca. She’s older than most of his “conquests”, with an air of authority, and she’s tougher and more sarcastic. She derides his attempts at small talk.

A little later, she’s undressing him. She expresses some disdain for how skinny he is, which disturbs him slightly. She undoes his jeans to go down on him anyway, but he stops her – he’s feeling a bit uncomfortable, and he’d rather be fucking her. But even that’s not much good, and as they fuck he finds himself losing his erection.

He starts to panic a bit – Rebecca tells him to keep going, but it isn’t working. He stops and rolls off her, sitting up against the wall, apologising. She’s furious, and when he asks for her help she refuses it. He begs her to help him – he really needs to get off now – but she’s just angrier and more disgusted. She leaves, slamming the door behind her.

After Rebecca leaves, Stirling gets up and dresses.

34

He walks the streets for a long time. He strides slowly but purposefully down the road towards an unspecified destination.

35

We see Jasmine walking around the supermarket. She has 3 bottles of wine and nothing else in the carrier. She looks vaguely at colourful items on the shelf before moving on.

36

It’s much later. Stirling is standing outside Jasmine’s house, staring up at it. The curtains are drawn, it looks pretty dark. He smokes a cigarette fretfully, then walks up the path towards it.

37

A minute later he’s climbing through a window into her living room. When inside, he moves quietly towards her bedroom. In the light from the bedside lamp he can see an empty, unmade bed. He steps in confidently, and is so very surprised to see Jasmine sitting around the corner, in the low light, drinking her wine and smoking her cigarettes.

She’s been thinking about Stirling and all the things that happened between them, both good and bad. She is very drunk. She has obviously been crying, but she isn’t now. She laughs almost mockingly to see him, as if she’d thought of summoning him magically and presto, he’s here.